Coordenadas Polares

Angel Carrillo Hoyo, Elena de Oteyza de Oteyza\(^2\), Carlos Hernández Garciadiego\(^1\), Emma Lam Osnaya\(^2\)

|

Coordenadas PolaresAngel Carrillo Hoyo, Elena de Oteyza de Oteyza\(^2\), Carlos Hernández Garciadiego\(^1\), Emma Lam Osnaya\(^2\) |  |

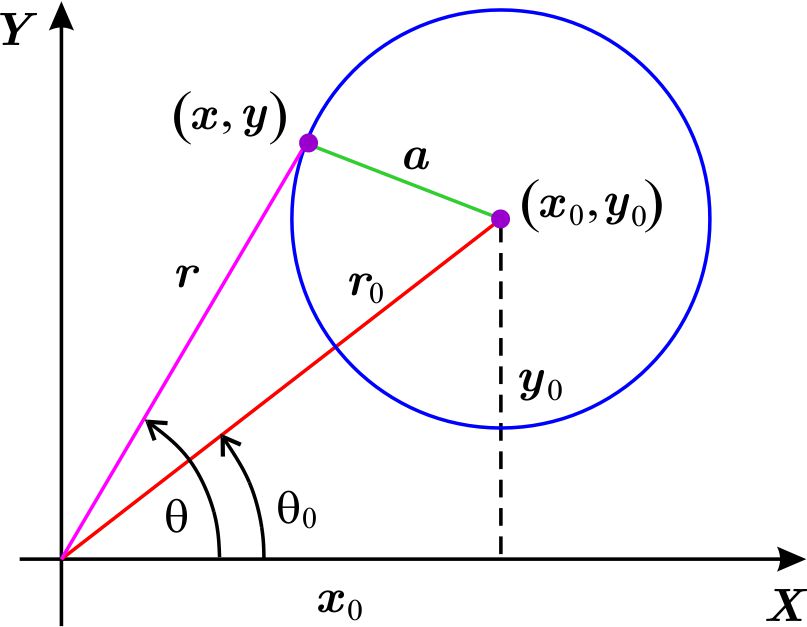

La ecuación de un círculo con centro en \(\left( x_{0},y_{0}\right) \) y radio \(a>0\) es: \begin{equation} \left( x-x_{0}\right) ^{2}+\left( y-y_{0}\right) ^{2}=a^{2} \label{circcart} \tag{4} \end{equation} es decir, \begin{equation*} x^{2}+y^{2}-2xx_{0}-2yy_{0}+x_{0}^{2}+y_{0}^{2}=a^{2} \end{equation*} Sean \(x=r\cos \theta \), \(y=r \ \text{sen}\ \theta \) y consideremos las coordenadas polares \(\left( r_{0},\theta _{0}\right) \) del centro \(\left( x_{0},y_{0}\right) .\) Entonces \begin{eqnarray*} x_{0} & = & r_{0}\cos \theta _{0} \\ y_{0} & = & r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0} \end{eqnarray*}

En general, la ecuación (\ref{circpolar}) es poco usada y la razón es, por supuesto, que la ecuación cartesiana (\ref{circcart}) que le corresponde es mucho más sencilla.

Veamos ahora algunos casos que sí aparecen frecuentemente.

entonces la ecuación es \begin{eqnarray*} \left( x-x_{0}\right) ^{2}+y^{2} & = & a^{2} \\ x^{2}-2xx_{0}+x_{0}^{2}+y^{2} & = & a^{2}. \end{eqnarray*} Sean \(x=r\cos \theta \), \(y=r \ \text{sen}\ \theta ,\) \(x_{0}=r_{0}\cos \theta _{0}\) y \(y_{0}=r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}.\) Sustituimos en la ecuación anterior, entonces \begin{equation*} r^{2}\cos ^{2}\theta -2rr_{0}\cos \theta \cos \theta _{0}+r_{0}^{2}\cos ^{2}\theta _{0}+r_{0}^{2} \ \text{sen}^{2}\theta _{0}=a^{2} \end{equation*} como \begin{eqnarray*} \left( x-x_{0}\right) ^{2}+y^{2} & = & a^{2} \\ x^{2}-2xx_{0}+x_{0}^{2}+y^{2} & = & a^{2}. \end{eqnarray*} y \begin{equation*} \ \text{sen}^{2}\theta _{0}=0, \end{equation*} entonces la ecuación polar del círculo es \begin{equation*} r^{2}-\left( 2rr_{0}\cos \theta \right) \left( \pm 1\right) +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2}, \end{equation*} es decir, \begin{equation*} \begin{array}{ll} r^{2}-2rr_{0}\cos \theta +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} & \text{si} \ x_{0} > 0 \\ r^{2}+2rr_{0}\cos \theta +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} & \text{si} \ x_{0} < 0 \end{array} \end{equation*}

Si además el círculo pasa por el origen, entonces \(r_{0}=a\) en cuyo caso la ecuación se simplifica todavía más \begin{equation*} r^{2}-\left( 2ar\cos \theta \right) \left( \pm 1\right) =0 \end{equation*} lo cual podemos escribir como \begin{equation*} \begin{array}{ll} r=2a\cos \theta & \text{si el centro está en la parte positiva del eje} \ X \\ r=-2a\cos \theta & \text{si el centro está en la parte negativa del eje} \ X \end{array} \end{equation*}

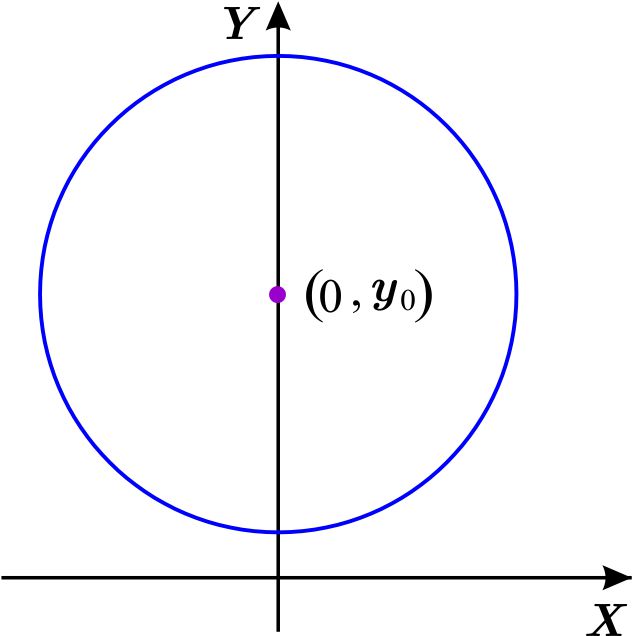

las coordenadas polares para el centro \(\left( 0,y_{0}\right) \) son: \begin{equation*} \left( r_{0},\theta _{0}\right) =\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \left( y_{0},\dfrac{\pi }{2}\right) & \text{si} \ y_{0}\geq 0 \\ \left( -y_{0},\dfrac{3\pi }{2}\right) & \text{si} \ y_{0} < 0 \end{array} \right. \end{equation*}

La ecuación polar del círculo es \begin{equation*} r^{2}-2rr_{0}\cos \left( \theta -\theta _{0}\right) +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} \end{equation*} como \begin{equation*} \cos \left( \theta -\theta _{0}\right) =\cos \theta \cos \theta _{0}+ \ \text{sen}\ \theta \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0} \end{equation*} y puesto que \begin{equation*} \cos \dfrac{\pi }{2}=\cos \dfrac{3\pi }{2}=0,\qquad \ \text{sen}\ \dfrac{\pi }{2}=1\qquad \text{y }\qquad \ \text{sen}\ \dfrac{3\pi }{2}=-1 \end{equation*} la ecuación en este caso es: \begin{equation*} r^{2}-\left( 2rr_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta \right) \left( \pm 1\right) +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} \end{equation*} es decir \begin{equation*} \begin{array}{ll} r^{2}-2rr_{0}\text{sen}\ \theta +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} & \text{si} \ y_{0} > 0 \\ r^{2}+2rr_{0}\text{sen}\ \theta +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} & \text{si} \ y_{0} < 0 \end{array} \end{equation*}

Nuevamente se obtiene una ecuación más sencilla si el círculo pasa por el origen. Así \(r_{0}=a\) en cuyo caso la ecuación es \begin{equation*} r^{2}-\left( 2ar \ \text{sen}\ \theta \right) \left( \pm 1\right) =0 \end{equation*} es decir, \begin{equation*} \begin{array}{ll} r=2a\ \text{sen}\ \theta & \text{si el centro es el origen o está en la parte positiva del eje} \ Y \\ r=-2a\ \text{sen}\ \theta & \text{si el centro está en la parte negativa del eje} \ Y \end{array} \end{equation*}

Ejemplos

Solución:

La ecuación es de la forma \(r=-2a \ \text{sen}\ \theta ,\) entonces es un círculo que pasa por el origen, su centro está en la parte negativa del eje \(Y.\)

Como \begin{eqnarray*} 2a & = & 5 \\ a & = & \dfrac{5}{2} \end{eqnarray*} es decir, el radio es igual a \(\dfrac{5}{2}\) y el centro está en \(\left( 0,-\dfrac{5}{2}\right) .\)

Solución:

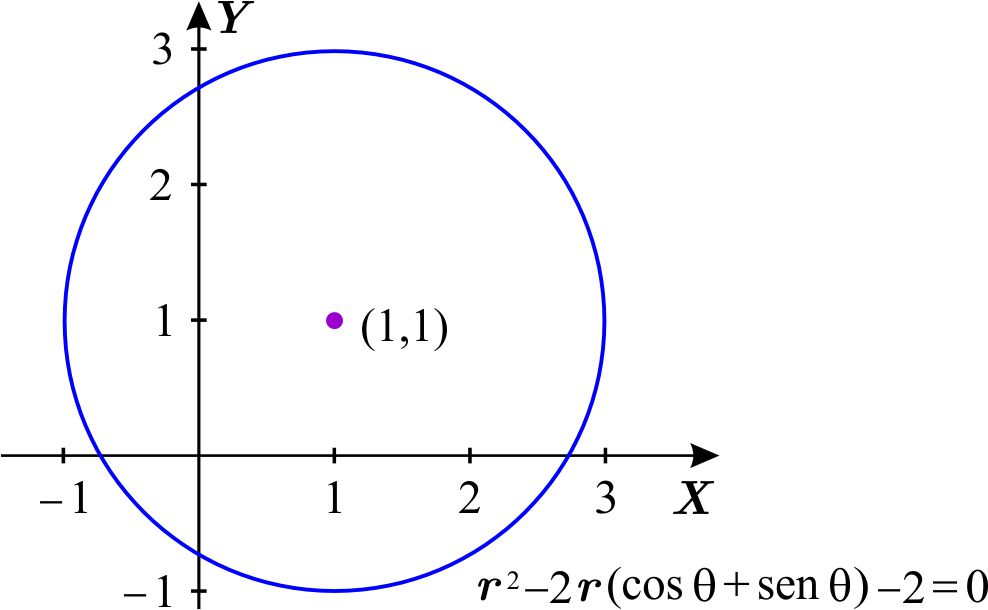

Tratemos de llevar esta ecuación a la forma general \begin{equation*} r^{2}-2rr_{0}\cos \left( \theta -\theta _{0}\right) +r_{0}^{2}=a^{2} \end{equation*} Queremos encontrar \(r_{0}>0\) y \(0\leq \theta _{0} < 2\pi \) tales que \begin{equation*} r_{0}^{2}-a^{2}=-2 \end{equation*}

y \begin{equation*} r_{0}\cos \left( \theta -\theta _{0}\right) =\cos \theta + \ \text{sen}\ \theta \end{equation*} Analicemos la segunda igualdad. Como \begin{equation*} \cos \left( \theta -\theta _{0}\right) =\cos \theta \cos \theta _{0}+ \ \text{sen}\ \theta \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}, \end{equation*} entonces \begin{equation*} r_{0}\left( \cos \theta \cos \theta _{0}+ \ \text{sen}\ \theta \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}\right) =\cos \theta + \ \text{sen}\ \theta , \end{equation*} de donde \begin{equation*} \left( r_{0}\cos \theta _{0}-1\right) \cos \theta +\left( r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}-1\right) \ \text{sen}\ \theta =0. \end{equation*} Puesto que la igualdad anterior debe cumplirse para cualquier valor \(\theta , \) en particular tenemos:

Eligiendo \(\theta =0\): \begin{equation*} \left( r_{0}\cos \theta _{0}-1\right) \cos 0+\left( r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}-1\right) \ \text{sen}\ 0=0, \end{equation*} es decir, \begin{equation*} r_{0}\cos \theta _{0}-1=0 \end{equation*} y tomando \(\theta =\dfrac{\pi }{2}\): \begin{equation*} \left( r_{0}\cos \theta _{0}-1\right) \cos \dfrac{\pi }{2}+\left( r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}-1\right) \ \text{sen}\ \dfrac{\pi }{2}=0, \end{equation*} de donde \begin{equation*} r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}-1=0. \end{equation*} Así, \begin{equation*} r_{0}\cos \theta _{0}=1\qquad \text{y} \qquad r_{0} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}=1, \end{equation*} igualando tenemos que \begin{equation*} \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}=\cos \theta _{0} \end{equation*} considerando \(0\leq \theta _{0} < 2\pi \) obtenemos

\begin{equation*} \theta _{0}=\frac{\pi }{4}\qquad \text{o} \qquad \theta _{0}=\frac{5\pi }{4}. \end{equation*} Entonces \begin{equation*} \cos \theta _{0}=\pm \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}= \ \text{sen}\ \theta _{0}, \end{equation*} de donde \begin{equation*} r_{0}=\pm \sqrt{2}. \end{equation*} Puesto que buscamos \(r_{0}>0\) \begin{equation*} r_{0}=\sqrt{2}. \end{equation*} Y como \begin{equation*} r_{0}^{2}-a^{2}=-2, \end{equation*} Sustituyendo los valores de \(r_{0}\) tenemos \begin{eqnarray*} 2-a^{2} & = & -2 \\ a^{2} & = & 4 \\ a & = & 2. \end{eqnarray*} Así, \begin{equation*} r_{0}=\sqrt{2},\qquad \theta _{0}=\frac{\pi }{4}\qquad \text{y}\qquad a=2. \end{equation*} Observa que la otra posibilidad \begin{equation*} r_{0}=-\sqrt{2},\qquad \theta _{0}=\frac{5\pi }{4} \qquad \text{y} \qquad a=2 \end{equation*} da como resultado el mismo círculo, entonces \begin{eqnarray*} x_{0} & = & \sqrt{2}\cos \frac{\pi }{4}=\sqrt{2}\left( \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \right) =1 \\ y_{0} & = & \sqrt{2} \ \text{sen}\ \frac{\pi }{4}=\sqrt{2}\left( \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2 }}\right) =1 \end{eqnarray*} es decir, es un círculo con centro en \(\left( 1,1\right) \) y radio \(2.\)

Hallar la ecuación en coordenadas polares del círculo que tiene centro y radio dados por